Introduction to the European Consensus Guideline for Phelan-McDermid syndrome

Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) (OMIM#606232) is a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by a deletion 22q13.3 a pathogenic variant in the gene SHANK3 that is located at 22q13.3.

In 2020, the Guidelines working group of the European Reference Network ITHACA (Intellectual disability, TeleHealth, Autism and Congenital Anomalies) established an international consortium of professional and lived experience experts representing 14 European countries (see Consortium), in order to update and adapt an already existing Dutch guideline to the European situation.

Aim of the guideline

The aim of the guideline is to provide recommendations for resolving the bottlenecks experienced in practice and to achieve more uniform and better-coordinated care for individuals with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Patient representatives were involved in the selection of topics and participated in writing the guideline. The recommendations are based on a careful weighing of the latest scientific insights and expert opinion. The guideline supports clinical decision-making and primarily targets those healthcare professionals involved in the care of children and adults with PMS, while also providing transparency to patients, parents and caregivers. A short practical version of the guideline (Clinical synopsis), a clinical surveillance scheme and emergency card and a lay version in different European languages have been made as well.

What does the guideline cover?

This guideline addresses issues for individuals diagnosed with Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS), due to a deletion 22q13.3 or a pathogenic variant in the SHANK3 gene. For the deletions, we specifically focus on deletions including SHANK3. This can be terminal or interstitial deletions and also includes deletions caused by unbalanced translocations or a ring chromosome 22. For clarity and because the majority of the data is available for genetic abnormalities affecting the SHANK3 gene, we focus on individuals with a SHANK3 haploinsufficiency (functional copy number loss), i.e. PMS SHANK3-related. Nonetheless parts of this guideline may be applied to deletions 22q13 not including SHANK3, i.e. PMS SHANK3-unrelated.

Methods

A survey exploring the most important topics and needs experienced by parents was developed and made available online in different languages (English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, German, Italian, Hungarian, Lithuanian, Swedish). Links to the survey were distributed among parents with the help of patient organisations. The survey was completed anonymously by the parents of almost 600 patients world-wide. The results can be found here.

The guideline is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II), which is an internationally accepted instrument and considered the most useful instrument to use in guideline development for rare disorders. After identification of the most important questions that needed to be addressed by the guideline, an extensive literature search was performed as described in the respective papers.

Each chapter of the guideline was critically reviewed by the consortium members, including the patient representatives. The final text was discussed in detail with all consortium members during a consensus meeting in June 2022 in Groningen, Netherlands, and the recommendations were rephrased until consensus was met. A voting process allowed each member to vote regarding the reliability of each recommendation.

Overview of topics of the European consensus guideline

For background information and the consensus recommendations we refer to the respective papers that have been published in the European Journal of Medical Genetics . The following topics have been addressed:

- Definition and clinical variability of SHANK3-related PMS (Schön et al., EJMG 2023)

- Counselling in PMS (Koza et al., EJMG 2023)

- Communication, language and speech in PMS (Burdeus-Olavarrieta et al., EJMG 2023)

- Chewing, swallowing and gastrointestinal problems in PMS (Matulevicienne et al., EJMG 2023)

- Altered sensory function in PMS (Walinga et al., EJMG 2023)

- Epilepsy in PMS (de Coo et al., EJMG 2023)

- Sleeping problems in PMS (San José Cáceres et al., EJMG 2023)

- Lymphedema in PMS (Damstra et al., EJMG 2023)

- Mental health issues in PMS (van Balkom et al., EJMG 2023)

- Organization of care in PMS (van Eeghen et al., EJMG 2023)

For information on the genetic background in PMS we refer to: Dissecting the 22q13 region to explore the genetic and phenotypic diversity of patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome (Vitrac at al., EJMG 2023)

Sustainability

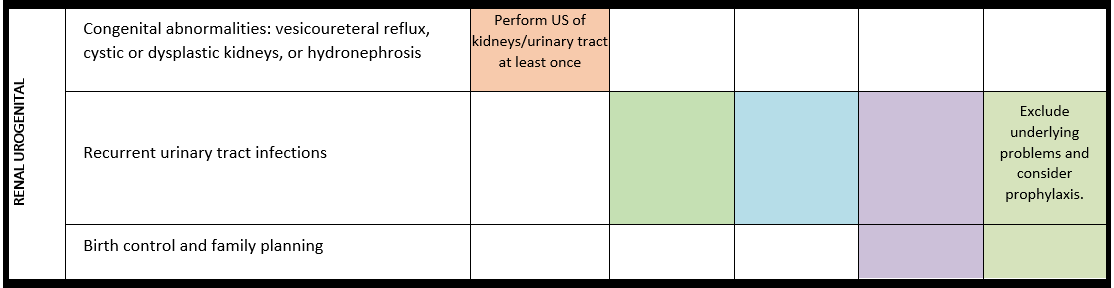

Not all clinical problems that occur in but are not specific for Phelan-McDermid syndrome are covered by the guideline and therefore no recommendations are given. However, whenever enough evidence was available they are mentioned in the surveillance scheme. E.g. the suggestion to perform a renal ultrasound, since renal abnormalities occur in 15% of individuals with a deletion 22q13.3.

New problems may occur and be published in case reports, that may warrant the attention of the clinician, even if there is no sound evidence yet. The PMS Guideline Consortium has agreed that the guideline will be updated whenever new information becomes available and as long as the Guideline Consortium exists. The most up-to-date version will be available on this website. An official revision of the guideline will take place upon request of and under the responsibility of the Guideline working group of ERN-ITHACA. Only after formal revision new information may result in new consensus recommendations.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the valuable input of all the European PMS consortium members. This guideline has been supported by the European Reference Network on Rare Congenital Malformations and Rare Intellectual Disability (ERN-ITHACA). More specifically by the Guidelines working group chaired by dr. A. van Eeghen. Osteba, the Basque office for Health Technology Assessment, assisted in the development and translation of the lay version of the guideline.

ERN-ITHACA is partly cofounded by the Health Program of the European Union. Funding was also obtained from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the EJP RD COFUND-EJP N° 825575.

Members of the European Phelan-McDermid syndrome guideline consortium

| Last name | First name | Country | affiliation/representing |

| Alhambra | Norma | Spain | Phelan-McDermid Association, Spain |

| Anderlid | Britt-Marie | Sweden | Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institutet and Department of Clinical Genetics, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden |

| Andres | Stephanie | Germany | Medicover München Ost MVZ, Humangenetik, Munich, Germany |

| Aten | Emmelien | Netherlands | Department of Clinical Genetics, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands |

| Barbosa Guedes | Rui | Portugal | Phelan-Mcdermid Association (Associação Síndrome Phelan-Mcdermid), Lisbon, Portugal |

| Bonaglia | Maria C. | Italy | Cytogenetics Laboratory, Scientific Institute, IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini, Lecco, Italy clara.bonaglia@bp.lnf.it |

| Bourgeron | Thomas | France | Human Genetics and Cognitive Functions, Institut Pasteur, IUF, UMR3571 CNRS, Université de Paris Cité, 75015 Paris, France |

| Burdeus-Olavarrieta | Monica | Spain | Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, IiSGM, Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain; School of Psychology, Universidad Autónoma, Madrid, Spain; |

| Carbin | Maya J. | Netherlands | Phelan-McDermid Association, Netherlands |

| Cooke | Jennifer | United Kingdom | Forensic and Neurodevelopmental Sciences Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience, King’s College London, United Kingdom |

| Damstra | Robert J. | Netherlands | VASCERN PPL European Reference Centre: Expert Center for Lymphovascular Medicine, Nij Smellinghe Hospital, Drachten, the Netherlands |

| de Coo | Irenaeus F.M. | Netherlands | Department of Toxicogenomics, Unit Clinical Genomics, Maastricht University, MHeNs School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, Maastricht, the Netherlands |

| Di Domenico | Stella | Italy | Uniphelan association Syndrome Phelan McDermid, Italy |

| Evans | D. Gareth | United Kingdom | Division of Evolution and Genomic Sciences, School of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, Manchester, UK. |

| Fernández-Fructuoso | José Ramón | Spain | Department of Pediatrics, Neonatology Unit. Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía, Cartagena, Spain |

| Grabrucker | Andreas M. | Ireland | Bernal Institute, University of Limerick; Dept. of Biological Sciences, University of Limerick; Health Research Institute (HRI), University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland |

| Gunnarson | Cecilia | Sweden | Department of Clinical Genetics and Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden. Centre for Rare Diseases in South East Region of Sweden, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden. |

| Hadzsiev | Kinga | Hungary | Department of Medical Genetics, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary |

| Hennekam | Raoul C | Netherlands | ERN ITHACA Guideline Working Group; Department of Pediatrics, Amsterdam University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands |

| Jesse | Sarah | Germany | University of Ulm, Department of Neurology, Ulm, Germany |

| Kant | Sarina G. | Netherlands | Department of Clinical Genetics, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. |

| Koza | Sylvia A. | Netherlands | University of Groningen, University Medical Centre Groningen, Dept. Genetics, Groningen, Netherlands |

| Kuiper | Els | Netherlands | Phelan-McDermid Association, Netherlands |

| Landlust | Annemiek M. | Netherlands | Autism Team Northern-Netherlands, Jonx, department of (Youth) Mental Health and Autism, Lentis Psychiatric Institute, Groningen, the Netherlands; University Medical Centre Groningen, Department of Genetics, Groningen, the Netherlands |

| Lapunzina | Pablo | Spain | Instituto de Genética Médica y Molecular (INGEMM)-IdiPAZ, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid; CIBERER, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Raras, ISCIII, Madrid; ITHACA-European Reference Network, Hospital La Paz, Madrid, Spain |

| Loth | Eva | United Kingdom | Department of Forensic and Neurodevelopmental Sciences, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, De Crespigny Park, London, UK |

| Mansour | Sahar | United Kingdom | SW Thames Centre for Genomics, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK and St George’s University of London, UK |

| Maruani | Anna | France | Excellence Center for Autism Spectrum & Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Inovand, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Department, Hôpital Robert Debre, Aphp, Paris, France; CRMR DICR, Rare Disease Center for Intellectual Disabilities, Defiscience, France |

| Mattina | Teresa | Italy | Department of Biomedical and Biotechnological Sciences, Medical Genetics, University of Catania, Catania, Italy; Scientific Foundation and Clinic G.B. Morgagni, Catania, Italy |

| Matulevičienė | Aušra | Lithuania | Dept. of Human and Medical Genetics, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania |

| Nevado | Julián | Spain | Instituto de Genética Médica y Molecular (INGEMM)-IdiPAZ, Hospital Universitario La Paz, Madrid, Spain; CIBERER, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Raras, ISCIII, Madrid, Spain; ITHACA-European Reference Network, Hospital La Paz, Madrid, Spain; |

| Parker | Susanne | Germany | (German representative of) Phelan-McDermid-Gesellschaft e.V. Geschäftsstelle Universitätsklinikum Ulm, Sekretariat Neurologie, Oberer Eselsberg 45, 89081, Ulm, Germany |

| Robert | Sandra | Swiss | (Swiss representative of) Phelan-McDermid-Gesellschaft e.V. Geschäftsstelle Universitätsklinikum Ulm, Sekretariat Neurologie, Oberer Eselsberg 45, 89081, Ulm, Germany |

| Sala | Carlo | Italy | CNR Neuroscience Institute, Milano, Italy |

| San José Cáceres | Antonia | Spain | Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Gregorio Marañón, Departamento de Psiquiatría del Niño y del Adolescente, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Salud Mental (CIBERSAM) and Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain |

| Schön | Michael | Germany | Institute for Anatomy and Cell Biology, Ulm University, Germany |

| Šiaurytė | Kamilė | Lithuania | Dept. of Human and Medical Genetics, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania |

| Stemkens | Daphne | Netherlands | VSOP – National Patient Alliance for Rare and Genetic Diseases, Soest, The Netherlands |

| Stiefsohn | Dominique | Austria | (Austrian) representative of) Phelan-McDermid-Gesellschaft e.V. Geschäftsstelle Universitätsklinikum Ulm, Sekretariat Neurologie, Oberer Eselsberg 45, 89081, Ulm, Germany |

| Swillen | Ann | Belgium | Center for Human Genetics, University Hospital Leuven; Department of Human Genetics, KU Leuven, Herestraat 49, 3000 Leuven, Belgium |

| Tabet | Anne C. | France | Cytogenetic Unit, Genetic department, Robert Debré Hospital; Human genetic and cognitive function, Pasteur Institute, Paris, France |

| Toro | Roberto | France | Patient representative, France |

| Turner | Alison | United Kingdom | Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation UK, 99 Highgate W Hill, London N6 6NR, United Kingdom |

| van Balkom | Ingrid D.C. | Netherlands | Jonx, department of (Youth) Mental Health and Autism, Lentis Psychiatric Institute, Groningen, Netherlands; Rob Giel Research Centre, department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands |

| van Buggenhout | Griet | Belgium | Department of Human Genetics, University Hospital Leuven, Belgium |

| van Eeghen | Agnies M. | Netherlands | ERN ITHACA Guideline Working Group; Emma Center for Personalized Medicine, Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam University Medical Centers, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Advisium, ‘s Heeren Loo, Amersfoort, Netherlands |

| van Ravenswaaij-Arts coordinator | Conny M.A. | Netherlands | University of Groningen, University Medical Centre Groningen, Dept. Genetics, Groningen, Netherlands; Autism Team Northern-Netherlands/Jonx, department of (Youth) Mental Health and Autism, Lentis Psychiatric Institute, Groningen, the Netherlands |

| van Weering | Sabrina | Netherlands | Beatrixoord Children’s Rehabilitation, University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG), Netherlands |

| Verpelli | Chiara | Italy | CNR Neuroscience Institute, Milano, Italy |

| Vignes | Stephane | France | VASCERN PPL European Reference Centre: French Reference Center Rare Vascular Diseases, Department of Lymphology, AP-HP, HEGP Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France |

| Vogels | Annick | Belgium | Centre for Human Genetics, University Hospital of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium |

| Vyshka | Klea | France | ERN ITHACA Guideline Working Group; ERN ITHACA Project management & Legal Office , Clinical Genetics Department, Robert Debré University Hospital, Paris, France |

| Walinga | Margreet | Netherlands | University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Dept. Genetics, Groningen, Netherlands |

Clinical synopsis of the European consensus guideline for Phelan-McDermid syndrome

This guideline is aligned with the latest research findings available as of May 2023.

Introduction

This is a shortened version of the European consensus guideline for Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS). More information including extended background information, methods and literature references can be found in the Special Issue of the European Journal of Medical Genetics published in 2023.

This guideline covers recommendations for individuals with SHANK3-related PMS, but may also partly be applicable for non-SHANK3-related PMS. It is written for professionals. A clinical surveillance scheme, emergency card and lay versions in multiple languages are available.

Phelan-McDermid syndrome

For detailed background information see: Schön et al., EJMG 2023.

Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) presents with a disturbed development, neurological and psychiatric characteristics, and sometimes other comorbidities. The incidence of PMS in European countries is at least 1 in 30,000, underdiagnosis being very likely. PMS-SHANK3 related is defined by the presence of SHANK3 haploinsufficiency, either by a deletion involving region 22q13. 3 or a pathogenic variant in SHANK3.

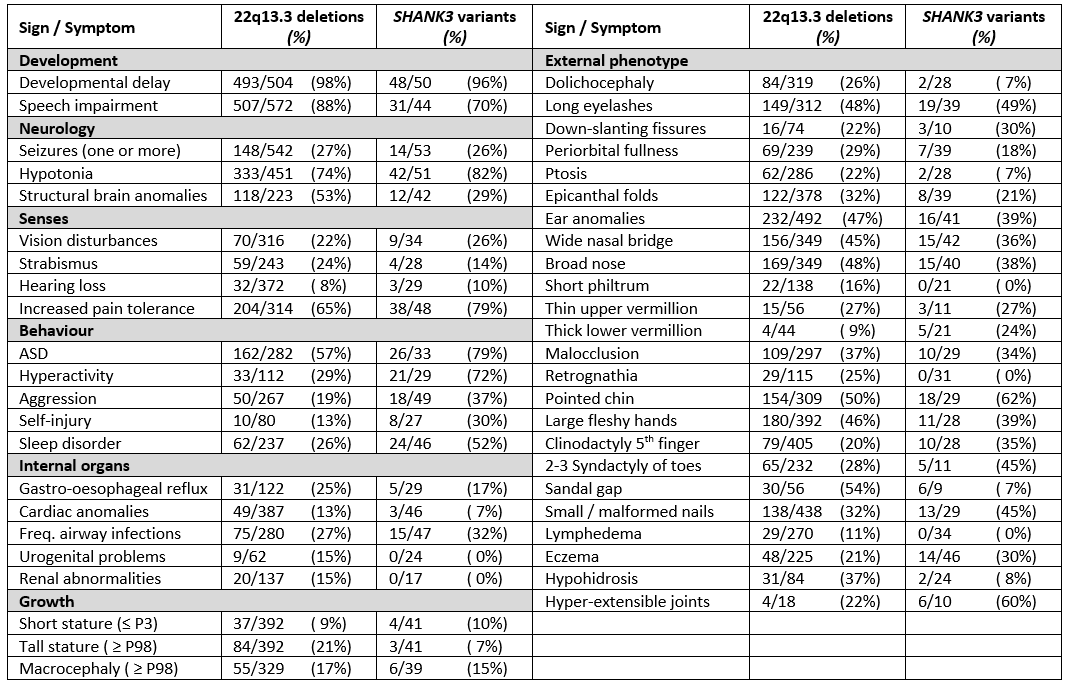

The phenotype of individuals with PMS is highly variable, depending in part on the deletion size or, whether only a variant of SHANK3 is present (table 1).

Table 1. Main phenotypic findings with frequencies in patients with PMS caused by a deletion of segment 22q13 (irrespective of the mechanism) and those caused by a SHANK3 variant. For references see Schön et al. 2023.

Results of clinical trials using insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-1), intranasal insulin, and oxytocin are available, other trials are in progress.

Enrolment in a clinical treatment trial may be considered and discussed with individuals with PMS (if possible) or their representatives.

Counselling in PMS

For detailed background information see: Koza et al., EJMG 2023.

A diagnosis of Phelan-McDermid syndrome requires genetic testing and most families will be referred to a clinical geneticist for counselling. Counselling will address the clinical picture and genotype-phenotype associations. If indicated, family members will be tested and- the risk of recurrence discussed. Most individuals have a de novo deletion or pathogenic variant. However, the 22q13.3 deletion could result from a derivate chromosome 22 of a parental balanced chromosomal anomaly. In rare cases, the deletion could be inherited from a parent carrying a deletion of 22q13.3, which can also be mosaic.

· All individuals with PMS and their parents (or direct relatives1) should be referred for genetic counselling. In genetic counselling, the clinical geneticist or other experienced clinician should explain the relationship between the genotype and phenotype (e.g. effect of deletion size or SHANK3 variant) and determine if there is an increased recurrence risk for another child with PMS for parents and other relatives.

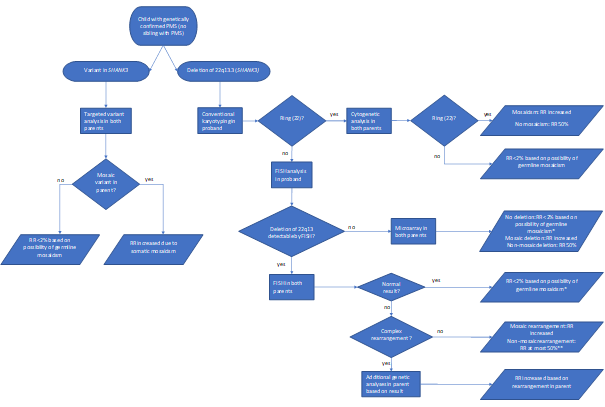

· After a diagnosis of PMS has been made, further genetic studies should be performed for proper genetic counselling (see Figure 1).

· Follow-up of individuals with PMS should include a check whether genetic work-up has been complete and up-to-date.

· In subsequent pregnancies, the parents of the child with PMS should be offered prenatal diagnostic testing.

1 In case of adult individuals with PMS and questions from siblings discuss also referral for genetic counselling.

Figure 1. Genetic follow-up testing in Phelan-McDermid syndrome

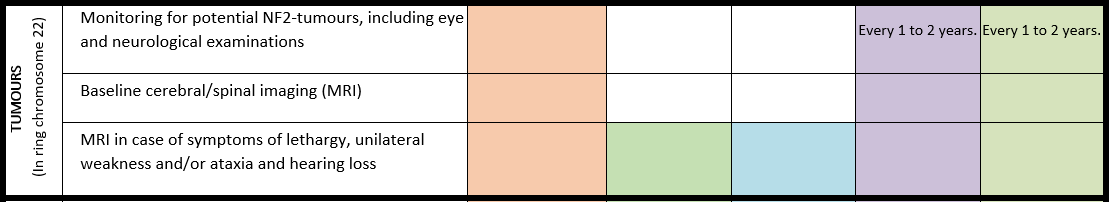

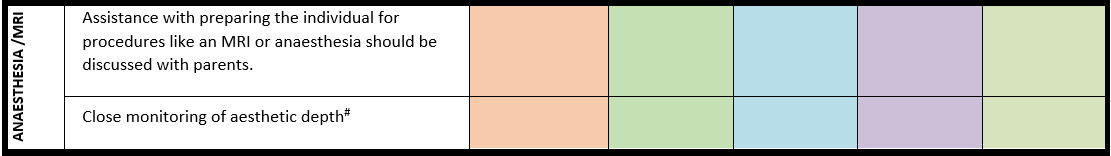

PMS due to a ring chromosome 22

For detailed background information see: Koza et al., EJMG 2023.

Few genotype-phenotype relationships have been reported. However, certain clinical characteristics distinguish Phelan-McDermid syndrome due to a ring chromosome 22 from a simple deletion 22q13.3. A ring chromosome 22 confers increased risk of NF2-related schwannomatosis (formerly neurofibromatosis type 2) and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumours associated with the tumour suppressor genes NF2 and SMARCB1, respectively, both located on chromosome 22. The prevalence of PMS due to ring chromosome 22 is estimated at 10-20%, while the risk of developing a tumour although not fully known is estimated at 2-4%. However, those who do develop them, often have multiple tumours.

· In an individual with a ring chromosome 22, personalized monitoring for potential NF2-tumors should be discussed with the patient or their representatives1.

· In an individual with a ring chromosome 22, cerebral imaging (MRI) is recommended at the age of 14 to 16 years, if not already available. In case of obvious hearing loss discuss with the patient or their representatives repeating of the MRI2.

1 There is currently no screening guideline, however, this may include annual hearing screening as well as eye and neurological examinations every 1-2 years starting between the ages of 15 and 20 years.

2 If the MRI is made under general anaesthesia, combine with spinal MRI. Discuss repeating the MRI every 5 years (in the absence of symptoms).

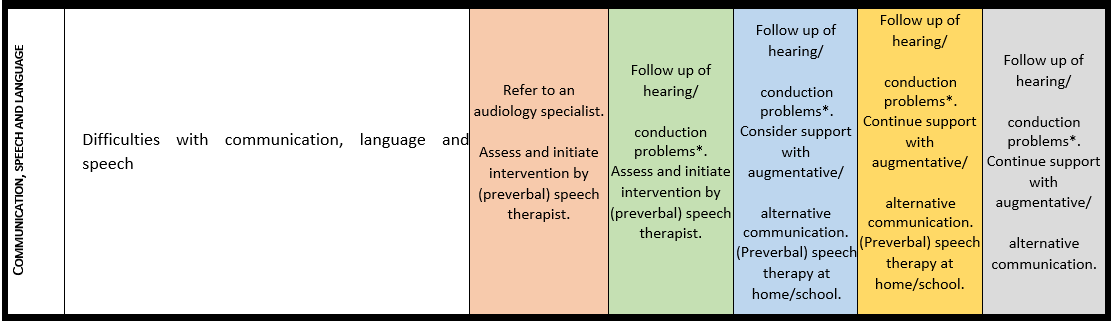

Communication, language and speech

For detailed background information see: Burdeus-Olavarrieta et al. EJMG 2023.

Marked speech impairment is present in up to 95% of individuals with a 22q13.3 deletion and in 69% with a pathogenic SHANK3 variant. Absence of speech affects 50%-80% of the individuals with PMS. Loss of language and other developmental skills is reported in around 40% of the individuals, with variable course. Deletion size and possibly other clinical variables (e.g., conductive hearing problems, neurological issues, intellectual disability…) are related to communicative and linguistic abilities.

· Hearing should be checked in every individual with PMS at the time of diagnosis and subsequently put into surveillance according to national guidelines.

· Every individual with PMS should be assessed by a specialized multidisciplinary team to evaluate all factors that may influence communication, speech and language.

· Preverbal and verbal communicative skills and cognitive development should be thoroughly evaluated in individuals with PMS prior to intervention and treatment.

· Parents of individuals with PMS should be counselled by a specialist on supporting, facilitating, and stimulating communication, language and speech from an early age on.

· Use of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) tools is recommended to facilitate communication for individuals with PMS when communication is limited; these approaches do not delay the active language development.

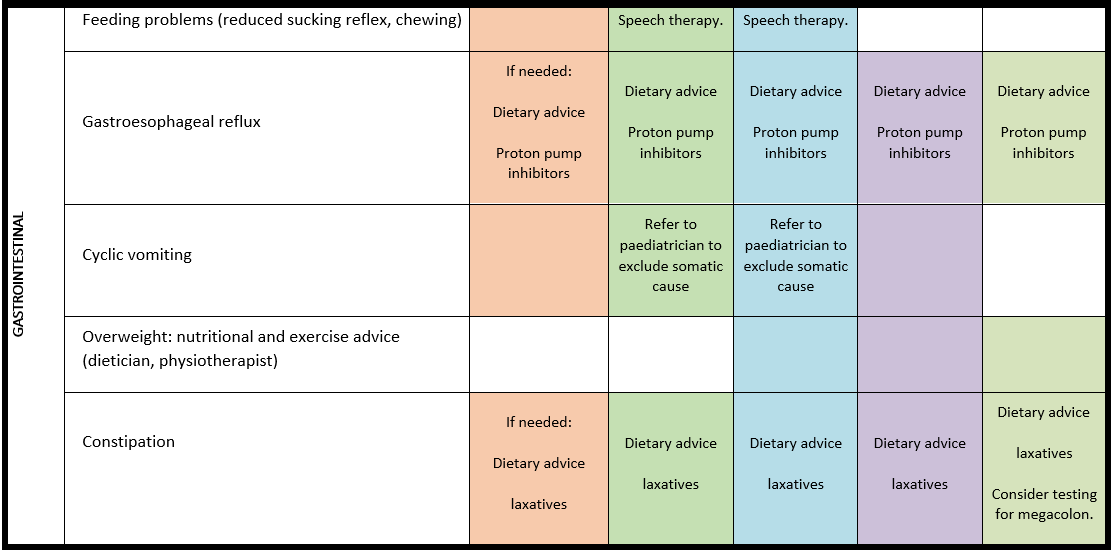

Chewing, swallowing and gastrointestinal problems

For detailed background information see: Matulevicienne et al., EJMG 2023.

Gastrointestinal (GI) problems are common in PMS. Chewing and swallowing difficulties, dental problems, reflux disease, cyclic vomiting, constipation, incontinence, diarrhoea, and nutritional deficiencies have been most frequently reported. To detect GI-problems in a timely fashion signs such as e.g. behavioural changes, sleep disorders, self-injurious mouthing behaviours should lead to investigation of possible underlying gastrointestinal causes. Gastrointestinal problems have a detrimental effect on the health of people with PMS and are a significant burden for their families.

· Both gastroesophageal reflux and constipation should be considered if behavioural changes are observed in individuals with PMS.

· In individuals with PMS, evaluation of faecal incontinence is advised. Somatic causes should be excluded, and behavioural modifications should be considered (if needed, a behavioural specialist should be consulted).

· For treatment of gastroesophageal reflux, diarrhoea and constipation in individuals with PMS, refer to general national or international guidelines.

· If zinc deficiency is present in an individual with PMS, dietary zinc supplementation should be considered.

· A referral to a pre-verbal speech therapist for chewing and swallowing disorders should be considered.

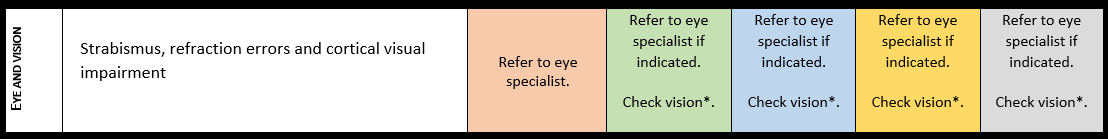

Altered sensory functioning

For detailed background information see: Walinga et al. EJMG 2023.

Altered sensory functioning is often observed in individuals with PMS. Compared to typically developing individuals and individuals with an autism spectrum disorder, distinctive features of sensory functioning in PMS exist, of which reduced responsiveness

to sensory input may lead to safety risks and as such is highly relevant for clinical practice. More hyporeactivity symptoms and less hyperreactivity and sensory seeking behaviour are seen, particularly in the auditory domain. Hypersensitivity to touch, possible overheating or turning red easily and reduced pain response are often seen.

· Caregivers and health care providers should be aware that individuals with PMS often have a reduced responsiveness to sensory stimuli such as pain, sudden sounds and heat. After every (suspected) trauma or physical incident the individual should be carefully examined.

· Every individual with PMS needs to be screened for hearing and visual disturbances at the time of diagnosis and subsequently put under surveillance according to national guidelines.

· Sensory integration functioning should be checked in every person with PMS using a validated screening instrument. If altered sensory function is present a sensory integration therapist should be consulted.

· In case of behavioural changes in individuals with PMS, evaluation of possible causes should include a search for pain and altered sensory function. The use of a validated non-verbal pain scale is recommended.

Epilepsy

For detailed background information see: de Coo et al., EJMG 2023.

Comorbid epilepsy is common in PMS and manifests itself in a variety of seizure semiologies. Further diagnostics using electroencephalogram (EEG) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are important in conjunction with the clinical picture of the seizures to decide whether anticonvulsant therapy is necessary.

· In every individual with PMS, irrespective of age, caregivers should be alert for seizures and epilepsy.

· In every individual with PMS in whom seizures are suspected but EEG studies are nonconclusive, overnight prolonged EEG studies should be considered.

· Brain imaging, preferably by MRI, is advised in every individual with PMS who has epileptic seizures, and indicated when new neurological signs and symptoms, including seizures, occur.

· A paediatric neurologist or neurologist should be involved in the therapy for epilepsy.

· Anticonvulsant treatment of epilepsy in individuals with PMS should be provided according to national guidelines.

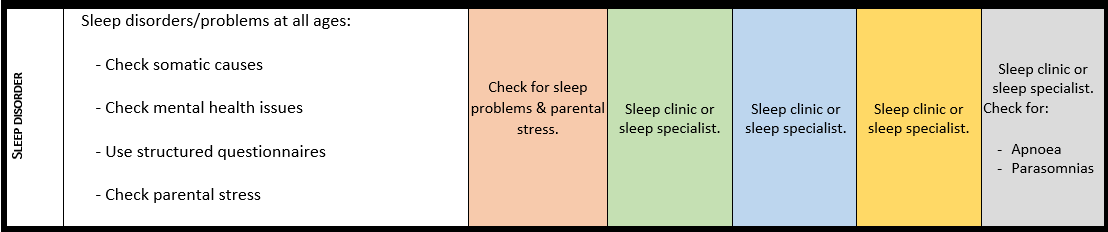

Sleeping problems

For detailed background information see: San José Cáceres et al. EJMG 2023.

Early onset sleep problems and disorders are reported in up to 90% of individuals with PMS. Not to be taken lightly, sleep problems and disorders may have a major impact on the health, behaviour, functioning and learning opportunities of affected individuals, as well as on the well-being and resilience of their parents and caregivers, ultimately affecting the whole household’s (mental) health and well-being. Country-specific prevalence rates reported ranged between 24% -46% of sleep difficulties. However, a world-wide survey amongst parents reported an alarming 59%. The main problems include difficulty falling asleep and numerous night awakenings. Also common are restless sleep, night-time incontinence and teeth grinding.

· Every individual with PMS and sleep problems should be evaluated for somatic, and/or environmental and/or neuropsychiatric causes.

· Mental health conditions co-occurring with sleep problems in individuals with PMS need to be investigated and treated.

· In individuals with PMS with sleep problems, sleep hygiene should be evaluated, and caregivers should be supported in establishing a structured approach (behavioural interventions).

· If sleep problems persist despite appropriate interventions, the individual with PMS should be referred to a specialist experienced in sleep problems or a specialist sleep centre.

Lymphedema

For detailed background information see: Damstra et al. EJMG 2023

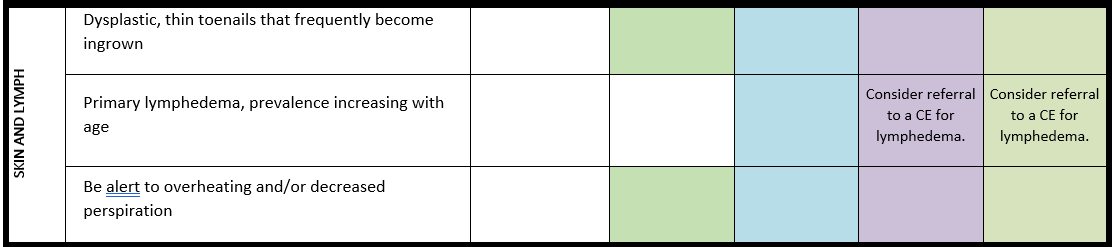

Lymphedema can be a clinical feature in up to 25% of the patients with PMS due to a 22q13 deletion and has thus far not been reported in individuals with a pathogenic SHANK3 variant. The mechanism causing lymphedema in PMS is unknown and it can be treated using existing general management guidelines, taking the functioning of the PMS patients into account.

· The health care provider should pay attention to the possible development of lymphedema in individuals with a 22q13 deletion, including ring chromosome 22, and start treatment (e.g., compression bandages and garments, skincare and advice) when needed.

· Refer individuals with PMS with lymphedema impacting daily functioning to a lymphedema centre of expertise for further investigations and treatment.

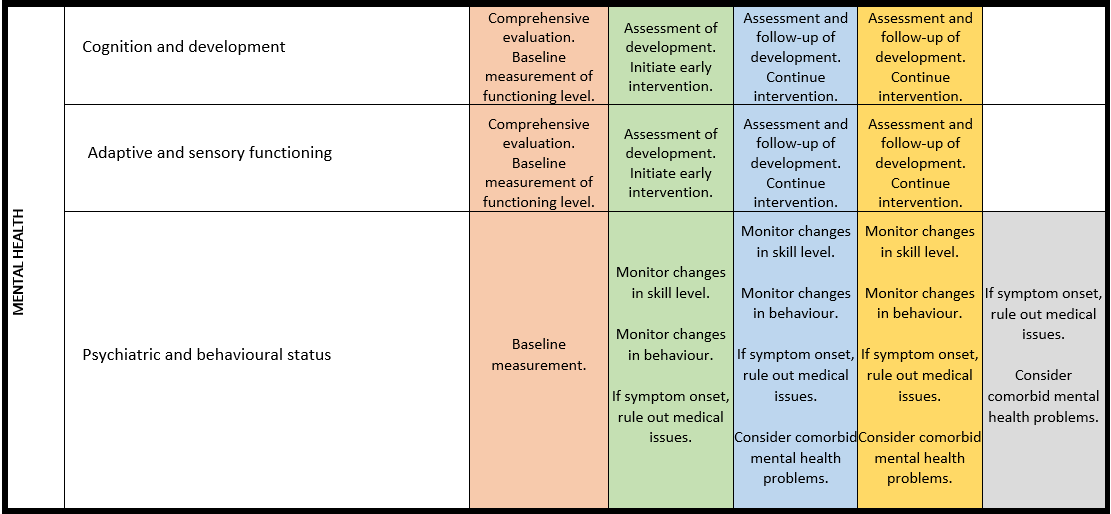

Mental health issues

For detailed background information see: van Balkom et al. EJMG 2023.

Behavioural problems and psychiatric comorbidities are common in PMS. It is important to consider developmental level of the individual with PMS when assessing mental health and behavioural issues. Understanding how the discrepancy between developmental level and chronological age may impact behaviours offers insight into the meaning of those behaviours and informs care for individuals with PMS. Taking factors of cognitive, developmental and adaptive functioning into account may enable clinicians to understand the meaning of behaviour, address unmet (mental health) care needs and inform treatment, thereby improving quality of life.

· At diagnosis for individuals with PMS a comprehensive evaluation should be made of factors influencing mental health, which include physical, psychiatric, psychological, developmental, communicative, social, educational, environmental, and economic domains, and general wellbeing as informed by caregivers.

· In individuals with PMS cognitive and socio-emotional level, communication, adaptive and sensory functioning should be assessed at diagnosis using appropriate tools, which may include a Functional Behavioural Assessment.

· In individuals with PMS a baseline measurement of individual functioning and skill level is useful, preferably in early childhood.

· Monitor behavioural status regularly including mood, affect, communication, interests and day/night routines in every individual with PMS, especially at important changes in daily environment, allowing early recognition of behavioural changes.

· Individuals with PMS who demonstrate noteworthy behavioural changes should be physically examined and evaluated for the presence of medical issues, including physical signs of abuse.

· If concerns are raised regarding mental health, functioning and behaviour of an individual with PMS, a psychiatric assessment is indicated to determine (comorbid) diagnoses, considering the developmental level of the individual.

Organization of care

For detailed background information see: van Eeghen et al. EJMG 2023.

The manifestations of Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) are complex, warranting expert and multidisciplinary care in all life stages. Assessment and care should consider all life domains, which can be done within the framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). This framework assesses disability and functioning as the outcome of the individual’s interactions with other factors. The different roles within care, such as performed by a centre of expertise, by regional health care providers and by a coordinating physician are addressed.

A surveillance scheme and emergency card are provided.

· Every person with PMS should receive PMS-specific care by a dedicated expert team, preferably in a centre of expertise.

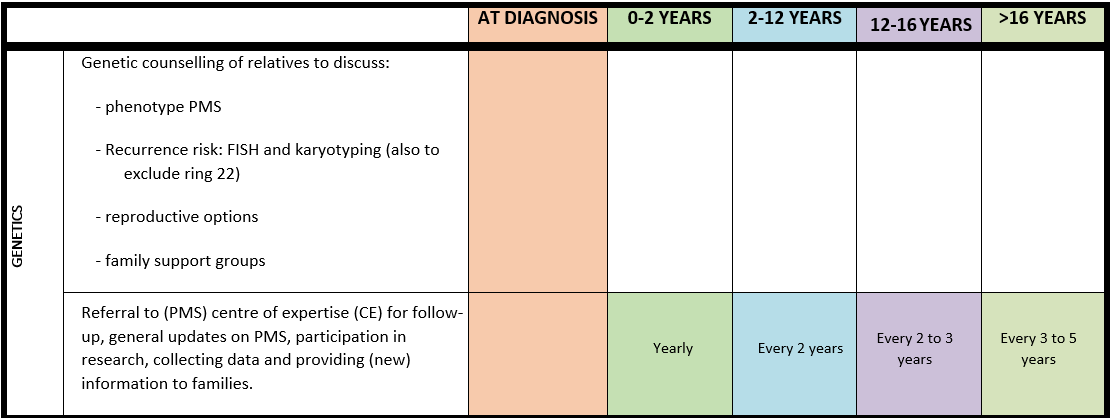

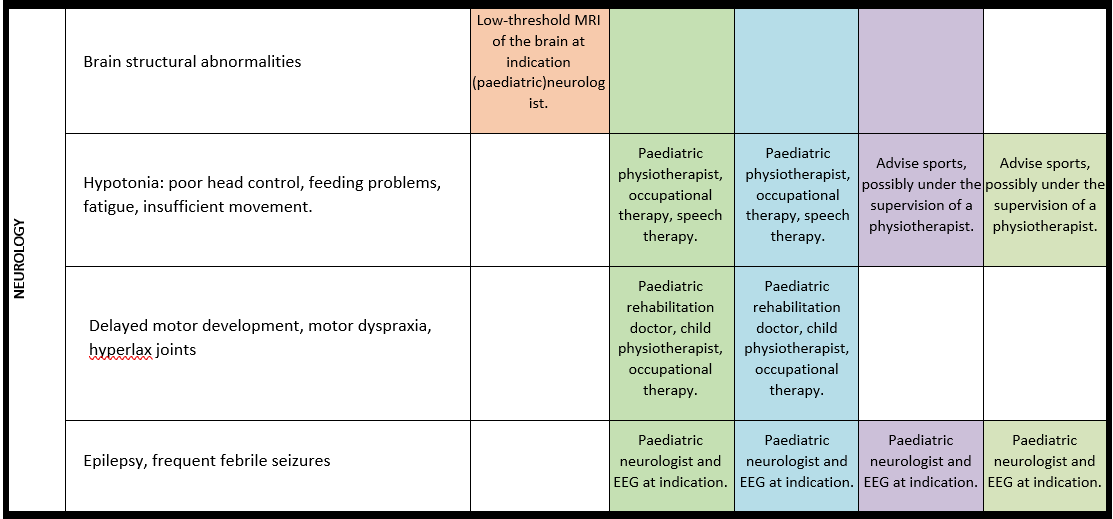

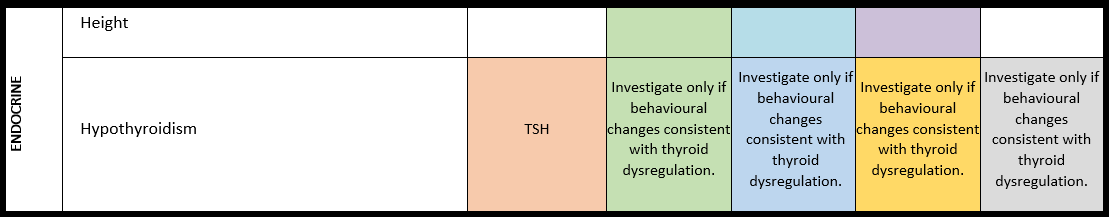

· A coordinating professional should initiate and monitor the multidisciplinary care for a person with PMS. The multidisciplinary team should be established based on the surveillance scheme (Table 2).

· For every person with PMS, specific care needs and the responsible professionals should be recorded in the medical records and the individual care plan, if available.

· For every teenager with PMS, the transition from paediatric to adult care is timely initiated and monitored by the coordinating paediatric professional. Coordinating should be transferred to a professional in adult care. This should be recorded in the medical records and individual care plan.

· Caregivers of individuals with PMS should be informed about the patient registry of the PMS when established.

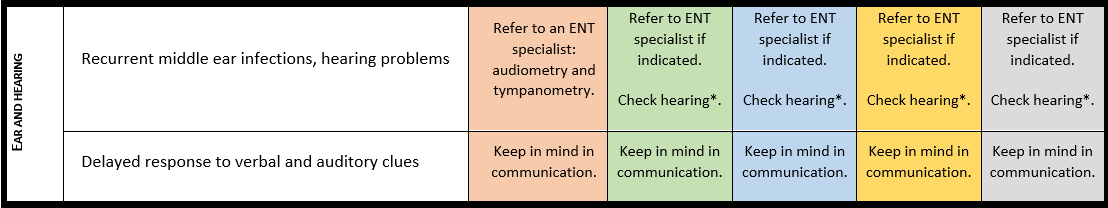

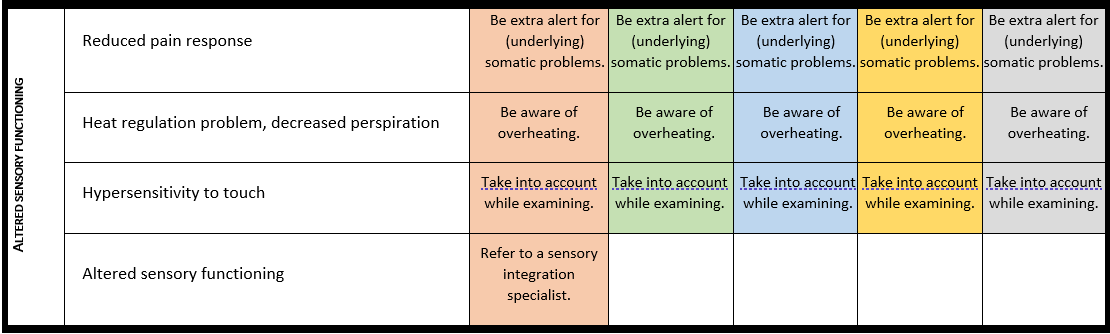

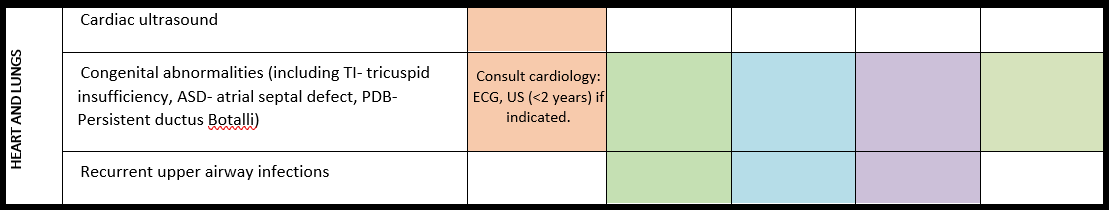

Surveillance scheme summarizing recommendations for follow-up of individuals with SHANK3-related Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS)

For background information see Special issue EJMG

General note: The coloured boxes in the scheme indicate when a specific check is recommended. The columns contain items that are advised at least once when making the diagnosis. For background information and further details see the relevant papers in this special issue, listed in the references. For prevalence of the clinical features see Schön et al (2023 this issue). All follow-up appointments may be more often when indicated.

ECG: electrocardiogram; EEG: electroencephalogram; US: ultrasound

* According to national guidelines

# Close monitoring of anaesthetic depth seems useful because there may exist an increased sensitivity to anaesthetics, based on hypersensitivity for isoflurane in Shank3-haploinsufficient mice (Li et al. 2017). However, to date there is no clear hint of anaesthesia complications in humans with PMS.

Booklet for families

Download below the guideline’s version for families in English, Dutch and Portuguese. More translations are to come.

Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Emergency Card

HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS INFORMATION ABOUT PHELAN-McDERMID SYNDROME (PMS)

General information

Phelan McDermid syndrome (PMS) is a clinically variable disorder, mainly characterized by intellectual disability (mostly moderate to severe), absent or severely delayed speech, behaviour that may include autism characteristics, and a variety of other signs and symptoms. Typically, PMS is caused by a deletion of chromosome 22, including band 22q13.33, or a pathogenic variant in SHANK3.

Listed below are the features that are important in an emergency situation. For a full overview of all features see Schön et al., EJMG 2023.

Frequently occurring problems (>30%)

Less frequently occurring problems (<30%)

- Developmental delay/Intellectual disability

- Marked speech impairment

- Hypotonia

- Decreased pain response

- Hypohidrosis*

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Hyperactivity#

- Sleeping problems#

- Regression

- Cyclical mood disorders

- Gastro-intestinal problems (constipation, diarrhoea)

- Dysmorphisms (a.o. long eyelashes, ptosis, broad nose, pointed chin, ear anomalies, malocclusion, retrognathia, large fleshy hands)

- Seizures

- Vision disturbances, including strabism

- Hearing loss

- Aggression against others and self

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux

- Cardiac anomalies

- Recurrent airway infections

- Renal anomalies/urogenital problems*

- Hyperextensible joints

- Lymphedema*

- Eczema

*only or mainly observed in deletions 22q13.3

#more common in SHANK3 variants

Acute life-threatening complications

- Seizures

- Burning accidents due to decreased pain response

- Complications due to gastro-oesophageal reflux

- Over-heating due to hypohidrosis

- Airway infections

Further information can be obtained from the International Phelan-McDermid syndrome Foundation and the Consensus guidelines on Phelan-McDermid syndrome, Special Issue EJMG 2023.

PHELAN-McDERMID SYNDROME EMERGENCY CARD (Updated __/__/20__)

PERSONAL DETAILS

Name_________________________________

DOB____________Gender________________

Address_______________________________

Phone_________________________________

COORDINATING PHYSICIAN DETAILS

Name_________________________________

Phone_________________________________

Email_________________________________

EMERGENCY CONTACTS

Name_________________________________

Relation_______________________________

Phone_________________________________

Email_________________________________

–

Name_________________________________

Relation_______________________________

Phone_________________________________

Email_________________________________

Typical vital parameters of patient

Oxygen saturation (%)____________________

Breathing rate (breath/min)________________

Heart rate (bpm)________________________

Blood pressure (mmHg)___________________

Temperature regulation___________________

Length/height (cm)________(___/___/20____)

Weight (Kg)_____________(___/___/20____)

Head circumference (cm)_____(___/___/20___)

( ) NG tube ( ) G-tube type and size_________

( ) Tracheostomy ( ) Mechanical ventilation_____

( ) Vascular access device _________________

Allergies_______________________________________________________________________

Major malformations

( ) Cardiac anomaly: type_________________

Last evaluation__/__/20__

Surgery no/date__/__/20__

( ) Structural brain anomaly: type_____ ______

Last MRI __/__/20__

Psychomotor development

( ) Normal ( ) Borderline ( ) Delayed

( ) hypotonia, degree ____________________

Cognitive development

Degree of delay: ( ) mild ( ) moderate

( ) severe ( ) profound

Verbal communication

( ) Absent ( ) Strongly limited ( ) Limited

( ) Near normal ( ) Normal

Behavioural problems

( ) Sleeping problems, type_________________

( ) Anxiety ( ) Aggression ( ) Self-injurious

( ) Hyperactivity ( ) Autism spectrum disorder

Likes:_________________________________ Dislikes:_______________________________

Medical complications

( ) Food intolerance: ( ) Lactose ( ) Gluten

Other________ Special diet__________

( ) Gastrointestinal reflux ( ) Cyclic vomiting

( ) Constipation ( ) Diarrhoea

( ) Hearing loss: ( ) sensorineural ( ) conductive

( ) mild ( ) moderate ( ) severe ( ) hearing aids

( ) Visual impairment: type_________ ( ) glasses

( ) Increased pain tolerance

( ) Pneumonia (recurrent), dates___________

( ) Ear infections (frequent) ( ) Sinus infections

( ) Renal/genital problems: type___________

( ) Hip problems: type___________________

( ) Lymphedema type___________________

( ) Dental anomalies: ( ) cavities ( ) crowding

( ) allows inspection

( ) Other medical problems: type_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Medical treatment

Medication Dosage Frequency Reason

_____________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________